Triathlon Bike Training When You Can’t Ride Outside

How does training for the bike leg of triathlon occur when you can’t ride outside? There are more opportunities than you might imagine.

It’s Getting Cold Outside

I woke this morning to an outside temperature of 11°F (-12°C) and new snow. On top of this, the fitness centers are closed because of COVID-19 restrictions.

I don’t have, nor do I intend to purchase, a fat tire bike for riding in the snow.

So, how can I maintain fitness for the bike leg of triathlons in which I hope to compete next spring?

There are plenty of options. While these may not be as good as going to a warm climate where I can ride outside, they still take away any excuses.

In this post, I will highlight the training I intend to use over the next several months to prepare for my next races.

Bike Trainer

The most common way of developing bike fitness without riding outside is to use a trainer. In most cases, you connect your road bike or triathlon bike to one of many styles of trainer.

One benefit of using a trainer is that you develop and maintain a familiarity with the bike you will use for your next triathlon.

When the fitness centers re-open, I will also use their stationary bikes both for individual sessions and classes. I prefer the latter.

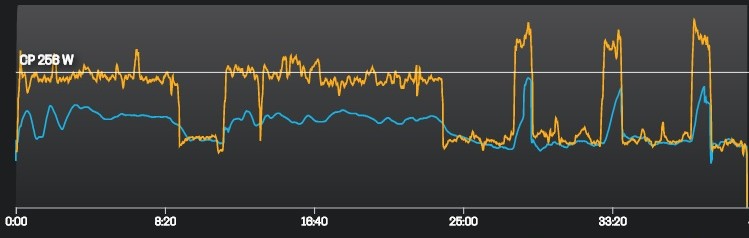

My trainer session, usually one hour, is divided into a few periods. Each segment is designed to work on a different goal. Breaking up the session also helps to prevent boredom. (Trainer sessions are also a great time to catchup on one of my favorite podcasts.)

A common one hour trainer session involves:

- Warm up – 10 minutes at a moderate pace, 80-90 rpm cadence.

- Single leg drill – 5 repetitions of 1 minute per leg at 80-90 rpm cadence – 10 minutes total. (NOTE: This may not be advisable for some trainers, but is for the Saris CycleOps Fluid2.)

- Intervals – 5 repetitions of 4 minutes in the highest gear in which I can maintain 60 rpm cadence followed by 2 minutes easy at 80-90 rpm cadence – 30 minutes total.

- Cool down – 10 minutes at moderate pace, 80-90 rpm cadence.

You can find many workouts to match your current fitness level and specific goals on-line or in books like “The Big Book of Bicycling” by Emily Furia and the Editors of Bicycling.

Advantages

- Safer than riding in traffic or in the aero position on winding trails shared with pedestrians, especially in the winter but really any time of the year.

- Efficient – A rule of thumb is that one hour on a trainer represents two hours riding on the road because you aren’t (or shouldn’t be) coasting on the trainer.

- Some training, such as single leg drills, are best done on a trainer.

- Accessible within your house or apartment.

Disadvantages

- Static trainers don’t help to develop stability and coordination or bike handling skills.

- Can be terribly boring. Some call these sessions the ‘purgatory’ of bike training.

Strength and Endurance Exercises

Strength training throughout the year should be a regular part of a triathlete’s training. I recommend Mark Allen’s program, especially if your fitness center is open.

However, if it isn’t or you want to give extra attention to strength training for the bike leg, look at the TrainingPeaks routine.

Except for the row, the exercises that involve weights can be done with homemade alternatives such as a weighted backpack (kettlebell) and plastic jugs filled with water (8 pounds per gallon/1 kilogram per liter) or other materials (beans, sand, coins) depending on the desired weight.

Advantages

- Allows you to focus on strengthening the weakest areas for the greatest improvement.

- Can be done from the convenience of home or at a fitness center.

Disadvantages

- The only disadvantage of which I am aware is that doing exercises without the benefit of a coach or training partner can lead to less than optimal results because of poor form.

Cross-Country Skiing

In the northern USA state where I live, Nordic skiing, or cross-country skiing, and ice skating are popular winter sports. I enjoy both skiing and skating, though have not skied for over 20 years.

Nearly every county park in our area has groomed cross-country ski trails. Larger parks also rent ski equipment (skis, boots, and poles) and offer group and personalized instruction.

Cross-country skiing produces endurance and strength for both the large muscles and the smaller muscles that support the larger muscles. Brett Sutton, coach of world champion triathletes, calls cross-country skiing “the hardest overall body workout out there”.

Downhill skiing is also good for building lower body and core muscle strength and for improving balance and coordination. However, downhill skiing does not yield the endurance benefits of cross-country skiing. Also, it much less accessible and more expensive than cross-country skiing.

“Nordic skiing, or cross-country skiing, is also great cross training for cycling. While downhill skiing brings more strength gains than endurance, Nordic skiing brings more endurance gains along with the added development of supporting muscles.”

ILoveBicycling.com

Classical vs. Skate Skiing

Today, there are two types of cross-country skiing – classical and skate-skiing.

Classical cross-country skiing involves a kick and glide motion. Skis remain parallel to each other, unless ‘snow plowing’. The classical cross-country ski courses are characterized by the parallel ruts in which the skis glide.

Cross-country skiing can also be done on fresh snow, that is, without a groomed trail. Most snow covered walking or bike paths are a candidate for classical skiing.

In contrast, the side-to-side motion in skate-skiing is like that of ice skating. Therefore, it uses muscles even more similar to those for pedaling.

One disadvantage of skate-skiing is that it requires a groomed trail. This makes it less flexible in where it can be done. Skate-skiing is also more difficult because it requires greater balance and coordination. However, it is faster than classical skiing.

Advantages

- Provides both endurance and strength benefits.

- Accessible – classical cross-country skiing can be done at your nearest park, golf course, or snow-covered lake. (Be sure the golf course is open for skiing and the ice on the lake is thick enough.)

- Relatively inexpensive, especially compared to downhill skiing.

- Gets you outside, into the fresh air and, hopefully, the sun. Think Vitamin D.

Disadvantages

- While cross-country skiing uses many of the same muscle groups as cycling, you may put more strain on certain muscles and tendons than when biking. To avoid injury, start slow and increase distance gradually.

- A beginning skier is likely to fall. Expect it and try to relax as you fall to avoid significant injury.

Note

From the reading I did in preparing this post, I have taken the first steps in scheduling cross-country ski lessons at a nearby county park. I am hoping to learn to skate-ski.

Ice Skating

Most cities in the northern climates, large or small, have an outdoor ice skating rink. Elsewhere, given the popularity of ice hockey, many of the more populated areas in the USA and Canada have indoor ice arenas.

Ice skating, like skate-skiing, is great for working smaller muscles that are often overlooked but valuable for biking performance. It is also great for improving balance, flexibility, and coordination.

Advantages

- Great for strengthening leg and abdominal muscles. Skating is also reported to increase the flexibility of more joints than cycling and running by strengthening ligaments and connective tissue around these.

- Low impact, unless you jump or spin (or fall often).

- Relatively inexpensive, often free (after purchasing or renting skates) if you live in a climate where outside temperatures are consistently below freezing. Even small towns typically have an outdoor ice skating rink open to the public.

- Gets you outside, into the fresh air.

Disadvantages

- Ice skating requires good ankle strength (which you probably have as a runner). However, you may put more strain on some muscles and tendons of the feet and ankles than when biking. As with any new sport, start slowly and increase gradually.

- Expect to fall, especially as you begin. At least that’s my experience. However, since I am usually bundled up for the cold, I have seldom been injured and then only with a bump or bruise to my ego.

No Excuses!

None of us has an excuse related to weather for not continuing to train for the bike leg of a triathlon throughout the winter. Even if I stay in the north part of the USA, there are plenty of opportunities inside and outside my house.

Some may actually be better than riding outside.

How Do You Train for Triathlon Biking When You Can’t Ride Outside?

How do you continue training for the bike when you cannot ride outside? Share your comments below.