Training to Run for Senior Triathletes

If you are among the tens of thousands of beginner or intermediate senior triathletes, this post about training for the run is for you.

Once you have a base level of aerobic fitness, it is time to add higher intensity to gain speed and endurance from your training. This post provides an overview of higher intensity run sessions. It also includes links to books with training plans you can use to prepare for your first or even your hundredth triathlon.

First, the Ground Rules of Run Training for Senior Triathletes

Before adding higher intensity to your training, it is important, even critical, to be aware of some of the key ground rules:

- Observe the 80:20 rule of aerobic to anaerobic (high intensity) training.

- Do not run all-out. Before beginning higher intensity sessions, run a 5k. Use your pace for this as the basis for the pace during high intensity portions. Most programs specify a pace for intervals that is below the race pace. A goal of the intervals, or even longer runs, is to use a pace that can be maintained throughout each of the repeats within a set.

- Avoid increasing distance and speed by more than 10% per week.

- Pay attention to running form.

More on these later in the post.

Start With Realistic Goals

Injury is the greatest risk when adding higher intensity to your run training. First, you are excited to get into the ‘real’ training. And, if you are like me, you imagine being able to run faster than your body is able.

Why do I say this? Because I have been there more times than I care to admit. Running too fast at this point usually leads to injury, enough to send you back to the start.

The best place to start is by using your last race time. However, if that has been more than a few months in the past, run the distance for which you are training. Use this time as the basis for the next 12 (sprint) to 18 (Ironman 140.6), or more, weeks leading up to a race.

Don’t Forget the Warmup

Every run session begins with 10 to 15 minutes to warm up the muscles. An easy jog will accomplish this. However, the warm-up will be even more effective using one or two of the following1,2:

- Strides – 80 to 100 yard (meter) runs at a fast but relaxed pace; gradually accelerate over the first three-fourths of the distance and decelerate to the warm-up pace during the rest of the distance.

- Butt kicks – 20 meters of running on the balls of your feet while trying to lift your feet high enough to kick yourself in the butt. These are often included in the first part of the strides. Butt kicks help with leg turnover speed, hamstring strength, and heel recovery.

- High knee lifts – These are also often included in the first part of each stride. For this drill, the goal is to lift your knees as high as possible with each step in order to increase leg turnover and strengthen calves and hip flexors.

- Skip – Combine jogging and skipping for 100 yards (meters) two or three times during the warm-up.

Types of High Intensity Runs

- Track repeats (or repeats on a relatively flat section of a paved or concrete trail) – these runs include distances of between 400 and 2,000 yards (or meters) followed by short periods of recovery. The distance of the repeat will gradually increase throughout the training program. The goal for these is to increase maximum oxygen consumption (VO2 max) and improve running efficiency, speed, and power.

- Hill repeats – According to the running power meter manufacturer Stryd, start with 2 x 15 to 20 seconds running up a hill with at least 8% grade (8 feet [meters] rise over 100 feet [meters] distance). Repeat every 7 to 14 days adding two repeats each session to a maximum of 10 per session.

Longer runs

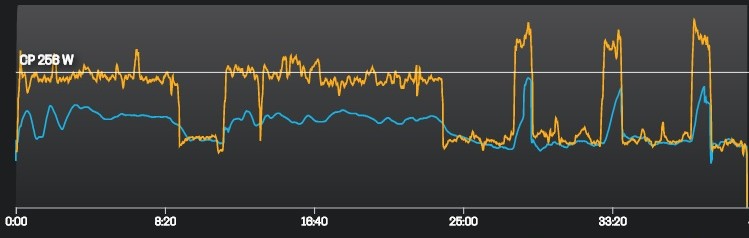

- Tempo runs – These are runs at a pace considered hard but still comfortable. Tempo runs are designed to increase anaerobic performance and, more specifically, the lactate threshold. The distance of these runs will vary with the distance of the race for which you are training and where in the training plan you are at the time. For example, the distances for tempo runs typically peak at about three-fourths of the way through a plan.

- Long runs – These are the longest but also the slowest runs. The aim of these is to increase aerobic endurance.

- Brick runs – These are runs of at least one mile immediately after a bike session. Brick runs train your body to run with good form after having completed the bike leg of a triathlon. Since this transition involves significant changes to body position (from the hunched over, aero or similar position to running), pay extra attention to your running form. An article on Training Peaks highlights typical problems with form when running after biking. It also describes the importance of proper running form in a triathlon using Olympic gold medal triathletes as examples.

Related post: Why Seniors Should Use Interval Training

Typical Run Training Session for Senior Triathletes

A high intensity run training session will consist of the following in order listed:

- Dynamic warm-up (NO STATIC STRETCHING of cold muscles!) for 10 to 15 minutes by jogging or combining jogging with one or two of the warm-up drills described above.

- Main set consisting of either repeats, tempo runs, or long runs.

- Cool down by jogging for 10-15 minutes. Proper cool down provides the benefits of active recovery.

- Stretching of warmed muscles immediately after completing the cool down portion of the run. This portion should include stretching the hamstring muscles, quadriceps, calf and Achilles tendon, and back.

The references at the end of this post contain detailed training plans for 5k (sprint) to full marathon (Ironman 140.6) distances.

Watch Your Form

Some books on triathlon training provide detailed descriptions of proper running form. These point to proper foot strike, head orientation, elbow angles, stride length, and so on. Kind of intimidating and too much for me to remember when I am running.

That’s why I appreciate that Joe Friel3 boils these down to simply ‘running proud’. You get most of the way if you think about looking proud – head high, standing tall, clearly defined steps, modest stride, etc.

Leave Your Questions and Comments Below

What have you learned to make your run training more effective? What is your favorite high intensity routine and why? Least favorite and why?

References

- Linda Cleveland and Kris Swarthout, Train To Tri – sprint and Olympic distances only (paid link)

- Bill Pierce, Scott Murr, and Ray Moss, Run Less Run Faster – 5k to full marathon (paid link)

- Joe Friel, Triathlete’s Training Bible – 5k to full marathon (paid link)