Training to Train – Building Aerobic Fitness for Senior Triathletes

This post is the first in a series about training for the beginner and intermediate triathlete age 50 and over. Its focus is creating aerobic fitness for senior triathletes. Originally published on September 17, 2020, it was updated on October 14, 2020 with additional test results.

The foundation for structured triathlon training is a solid base of aerobic fitness. Even elite athletes typically begin each new season with a ‘base phase’.

In Train To Tri: Your First Triathlon, (paid link) the Base Phase is defined as “the period during a training cycle where basic endurance is the focus, normally in the beginning of the season.”

Look at training plans for triathlon or for the individual sports of a triathlon. In most of these, you will read about ‘base building’ or something similar.

But what does ‘building a base’ mean? And, how does one go about it? More specifically, how do senior triathletes develop this base level of aerobic fitness?

While there is plenty of discussion about the need to achieve a base level of fitness before beginning structured training, there is seldom detail on how this is done. The closest advice I had previously found was to train at ‘low to moderate intensity’ for one to two months at the beginning of the season.

I need something more specific. And, I need to know when I have completed the Base Phase.

Following is information about the plan I have started to use for the aerobic base building phase. I believe it answers these two needs.

Aerobic Fitness is the Foundation for High Performing Senior Triathletes

During the three decades of the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, eastern European athletes dominated endurance sports by adopting training programs in which the training stresses were varied throughout the year.

In the 1960s, this concept was refined and formalized by Dr. Tudor Bompa of the Romanian Institute of Sports. His research, which led to him becoming known as the “father of periodization’, helped eastern European athletes dominate sports on the world stage.

This domination by the eastern Europeans ended when athletes across the rest of the world learned about and adopted periodization.

Periodization is based on the idea that training is most effective when it progresses from general to that specific to the athlete’s main sport. In the context of triathlon, this means starting with building a solid base of endurance before focusing on performance, that is, speed and distance, in swimming, biking, and running.

Why Senior Triathletes Need to First Develop an Aerobic Fitness Base

I understand. You are eager to get out and train hard. Besides, who wants to spend two months plodding along in the run. Isn’t ‘No pain, no gain’ our mantra?

I am constantly reminded that patience is not only a virtue but one of the triathlete’s best friends. Here’s why senior triathletes need to start by developing aerobic fitness.

Minimizes injury while building strength

Combined with strength, a base level of aerobic fitness for senior triathletes is our main antidote to injury.

The wisdom of the ‘No pain’ philosophy has come into serious question. I certainly no longer buy this. My impatience has nearly always led to injury or at least enough fatigue that training is not consistent.

This is supported by Coach Parry who provides the “Faster After 50” training program. In a video interview, Coach Parry gave the top five tips for starting to run after age 50.

Interestingly, his number 1 tip is to “walk before you run”. This approach has the combined benefit of (1) building aerobic fitness and (2) strengthening body parts such as tendons that are most subject to injury.

Building aerobic fitness and strength combine to gradually prepare the body to minimize, if not avoid, injury when eventually subjected to higher intensity training.

Results in more effective race specific training

Secondly, without a base level of aerobic fitness, we will not have the endurance needed to execute the high intensity workouts required to increase our performance. Without an aerobic base, we will never be a serious contender in a sprint triathlon, never mind a longer distance race.

As a result of inconsistent training due to injury and fatigue, my aerobic endurance had become sub-standard. Even though I usually ran 3 days per week, most of the time my heart rate was well above the aerobic zone.

That my aerobic fitness needed improvement was confirmed earlier this year when I started running with a Stryd power meter. My results, displayed in the Stryd Powercenter app, showed that my strength was well above average for my age. However, my fitness, fatigue resistance, and endurance were all below average.

In short, I was able to run fast enough in hill repeats and short sprints, just not for very long.

I decided to take a step back and work on my aerobic fitness.

Developing Aerobic Fitness for Senior Triathletes

The base level of aerobic endurance is developed through an extended period of moderate level physical activity. This is activity that our bodies can eventually sustain for hours since it is fueled by fat, something of which we all have plenty.

But, how do you know what is ‘moderate’?

One approach is to limit one’s pace by breathing only through the nose. A second guide is to limit one’s running pace to that at which you are able to maintain a conversation.

A more objective approach is to use a heart rate monitor. Today, these are available as a chest strap connected to a smartphone or watch, a sensor built into a sports watch that measures heart rate at the wrist, and, more recently, as a sensor built into earbuds.

What is the heart rate at which you should be training to most effectively build base aerobic fitness?

Training with a heart rate monitor – the CDC method

There are different approaches to developing the aerobic endurance base using a heart rate monitor (HRM).

The United States Centers for Disease Control (CDC) defines the target heart rate for moderate-intensity physical activity rate based on age. Following is the CDC calculation of heart rate range with an example for a 70-year-old person.

- Subtract your age from 220.

- Example: For a person age 70, the maximum heart rate is 150 (220-70 = 150) beats per minute (bpm).

- Next, multiply the maximum heart rate by 64% and 76% to obtain the lower and upper limits of the heart rate range for moderate-intensity physical activity. In our example for the 70-year-old person, these limits are:

- 64% value: 150 x 0.64 = 96 bpm

- 76% value: 150 x 0.76 = 114 bpm

In summary, the CDC method shows that a person age 70 should maintain a heart rate between 96 and 114 bpm during a period of moderate-intensity physical activity.

Training with a heart rate monitor – the MAF method

An approach that is more specific to triathletes is the MAF (Maximum Aerobic Function) method developed by Dr. Phil Maffetone. Dr. Maffetone was the coach for six-time World Ironman Champion, Mark Allen, so I consider him credible.

The MAF method promotes building a healthy aerobic system based on managing three components: exercise, nutrition and stress.

Part of the Maffetone approach is MAF-180 for calculating the aerobic zone heart rate range, also based on age. However, the calculation is even simpler.

Applying this method, our active 70-year triathlete will train with a maximum heart rate of 180-70 = 110. The lower end of the training range is 10 bpm below the maximum.

So, using the MAF method, the heart rate range for our 70-year triathlete during the base building phase is 100 to 110 bpm.

Putting it in practice

In my first use of this method, I followed a program of running/walking five days per week. On the other two days, I cross trained with biking, swimming, and kayaking. Except when swimming, I wore a heart rate monitor chest strap synced to my Garmin watch. Throughout each session, I would adjust my pace to keep my heart rate within the rate recommended in the MAF method.

As predicted by Dr. Maffetone, the time to complete the second mile was longer than the first mile, and so on. However, the time to complete each mile gradually decreased over the period. This was evidence that my aerobic fitness was increasing.

When Should You Consider the Base Period Complete?

Most training programs will recommend a base building period of up to two months. This assumes training within the aerobic heart rate range for 5 to 7 days per week along with adequate rest and proper nutrition.

For a new runner, the authors of Run Less, Run Faster (paid link) prescribe a “3-month base training” program that combines running and walking. Once this is complete, the runner would begin their training plan.

If you are anything like me, you want something more definitive. Joe Friel in The Triathletes Training Bible (paid link) describes a numerical approach to determine when the base phase can be considered complete.

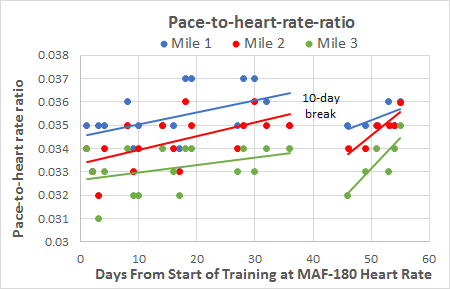

Friel’s method uses a ratio of pace (run) or power (bike or run) to heart rate for segments of a fixed run or bike course. Results are pictured in the next section in a second graph below that for Pace.

When this ratio for the first portion of the session is consistently within 5% of the ratio for the second portion, you have arrived at the end of the Base Phase.

Use the Comments section below to request a copy of the Google Sheet that includes these calculations.

Results of Aerobic Fitness Training with the MAF-180 Plan

The original post was published after 28 days with the program after which I continued the plan. However, after 36 days, I took a 10-day break from any exercise as a result of illness and cold, rainy weather. I then re-started the program with some unexpected results discussed and pictured below.

course while maintaining heart rate in the prescribed range.

same 3.5 mile course while maintaining heart rate in the prescribed range.

Lessons From The First Two Months

Data from the MAF-180 program normalized using Joe Friel’s approach has shown me the following:

- The downward trend in pace over time is as anticipated by Dr. Maffetone. So is the increase in time for successive miles.

- There is considerable day-to-day variation in pace. These result from external (e.g. temperature, humidity, wind) and internal (e.g. hydration, degree of recovery from the previous day) factors.

- Fitness is fragile. A ten-day break almost completely erased the gains from the previous 28 days.

- Don’t lose hope. Even if fitness appears to disappear quickly with a break, it will recover quickly after a short break. The pace and pace-to-heart rate ratio graphs show a greater slope after the break. They also converge much faster in the days after the break. Presumably, this is because I had retained some of the previous aerobic fitness.

- Pace-to-heart rate ratio appears to be a better metric than pace alone.

Where Do You Go From Here?

With a proper aerobic endurance fitness base, you can now proceed to higher intensity workouts. These build the anaerobic system and increase performance.

After completing the base phase, gradually increase the intensity of your exercise. This is especially true if you are planning to race. For example, you can add speed drills into your swimming, biking, and running sessions.

However, even then, the consensus among trainers is to maintain an 80:20 ratio of aerobic (moderate intensity) to anaerobic (high intensity) training. And, also heed the rule of thumb of not increasing the intensity or duration of a session by more than 10% per week to avoid injury.

What Is Your Experience and Approach To Building Aerobic Fitness?

Share your thoughts and questions about aerobic training in the Comments section below.

Don’t forget to request a copy of the Google Sheet that includes the calculations and graph templates if you want to run a similar test.

Thank you for a very informative article. I am interested in obtaining the google sheet with calculations if possible. Thanks. Phil

Thank you for the comment. I have shared a copy of the Google Sheet with you using the email address you gave. I will be happy to help with any questions or issues.