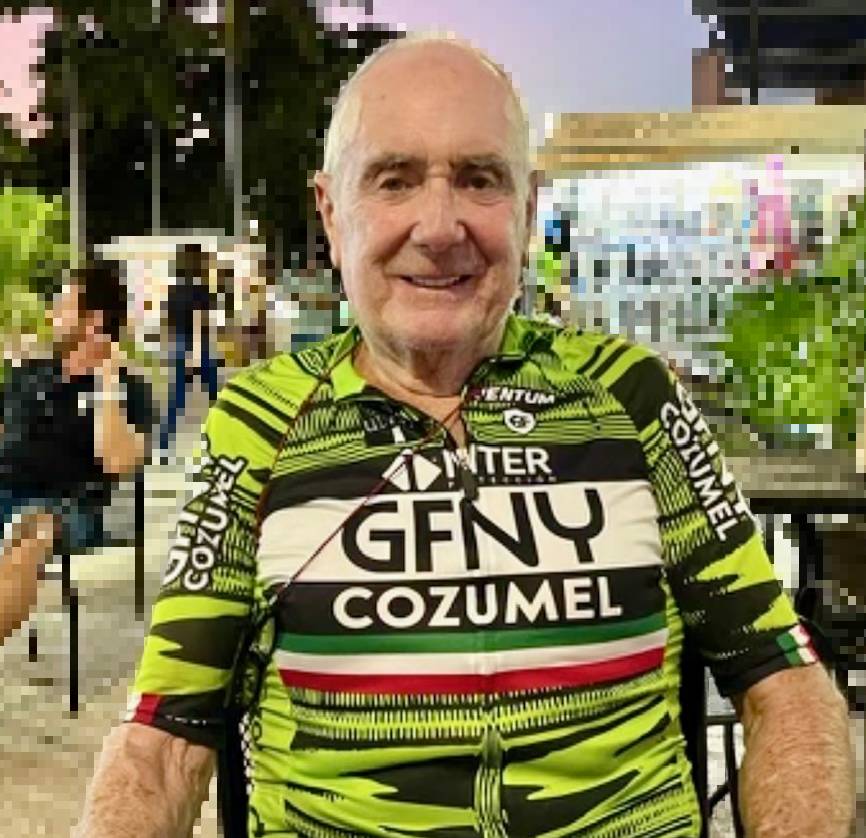

Changing His Mind – Howard Glass’ Story

Older adults give many reasons for beginning or continuing to train for and compete in triathlons. Senior triathlete Howard Glass is the first person to tell me how triathlon changed his mind, his thoughts.

Prologue

Following our hour and a half phone call during the evening of Tuesday, September 4th, Howard Glass and I agreed to resume our conversation after I had finished a draft of his triathlon story. However, before we talked a second time, Howard’s daughter, Lydia, replied to my email to Howard, informing me that her dad had unexpectedly passed away on September 9th.

While Howard’s passing impacted some of what I had included in my first draft, the principal message from his story stayed the same. Howard openly shared about the struggle that eventually sparked his love of triathlon. I hope my record of our conversation will inspire you as much as he did me. He was a remarkable man.

Introducing Howard Glass

Howard began telling his triathlon story by recalling his move to the United States from the UK, where he had spent the first part of his life working in the real estate industry. After falling in love with the Florida Keys during his first visit to the USA in 1991, Howard purchased a wooded lot in the Keys in March 1992. His plan was to build a home here for him, his first wife, and daughter Lydia.

He returned to Florida three days after Hurricane Andrew in August 1992, to complete plans for the house with an architect. In November, he and a builder he had hired broke ground on the project.

While in Florida, Howard worked alongside the builder to help complete the family’s new home. However, since he was in the country on a tourist visa, Howard was required to return to the UK every 90 days. As a result, the house took two years to complete.

Eventually, Howard received a green card, which allowed him to live full-time and work in the USA. He and his family moved to their new home in Florida, and he began working at Home Depot.

Cycling, A Life Changer

I asked Howard what his experience with endurance sports was before training for triathlon. His one-word answer was, “Zero.”

Before beginning to train for his first triathlon in 2009, Howard said, “I had never run before, had never had a bike before, and I could swim a little.”

So, what caused Howard to train for a triathlon? Following personal events that led to him moving to Palm Beach Gardens, Florida, Howard says he developed severe depression. He began taking medication to treat his depression.

For helping a realtor friend work on her house, she and her two brothers bought Howard a road bike. As he began riding, he found the depression lifting. After about three months, he had weaned himself off the medication.

Howard carried this experience with him. He remained convinced that the combined benefits of exercise and his focus on triathlon kept the depression away.

Related Post: Triathlon For a Healthy Brain – Pat & Joan Hogan’s Story

First Triathlon at Age 68

Howard continued biking, then added running and swimming to his exercise routine as he trained for and completed a Sprint triathlon in Jupiter, Florida, in 2009.

Over the next two years, Howard did a couple more Sprint triathlons. In 2010, his finished his first Olympic distance triathlon in Miami, Florida.

“Like an idiot, I thought I could do the Disney half Ironman in June. This race taught me I needed to hydrate, especially in Florida during the summer. But I didn’t know how to hydrate. After the bike, which I finished with an average speed of about 18.5 miles per hour, I found I couldn’t change gears to run the half marathon.”

Recognizing that Howard was dehydrated, race medical staff brought out a stretcher, which they used to move him into a tent. Howard said, “They gave me a couple of bags of IV fluid. Suddenly, I felt great, so I asked if I could get back into the race.”

Their answer was clear: “You’re done.” That was Howard’s first experience being severely dehydrated.

A few months later, in October, Howard took another shot at the half Ironman distance, the Atlantic Coast Triathlon in Amelia Island, Florida. The flat bike and run courses led to his best time for a half Ironman, 6 hours, 11 minutes. A month later, he did a second half Ironman in Miami, Florida.

Howard Becomes An IRONMAN

After finishing this race, he packed his bike and flew with it to Seattle, from where he rented a car and drove east across Washington state to Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, for his first full Ironman. He arrived two days before the race. The first morning, he went to the lake where the swim would take place, put on his wetsuit, and went for a short swim in the 53°F water.

The short practice swim did not prepare him for the full, 2.4-mile swim during the triathlon. For the race, the swim involved two loops of a 1.2-mile course. After completing the swim, he went into a tent with heaters to warm up. After warming, he went out on the bike leg in a short-sleeve shirt in the 45°F air. He admitted to knowing nothing about aid stations. He finished the bike leg, then fast walked the run course, finishing just before midnight. After collecting his bike and packing it in the car, Howard returned to the hotel for a warm shower.

His First Kona Slot

The next day, he returned for the banquet and awards ceremony, where he collected his first Ironman finisher medal and second place age group award. This result, especially on a tough course, gave Howard a lot of confidence.

Over the next four years, Howard completed another five full Ironman distance triathlons. One of these was the 2012 Ironman Lake Placid (Lake Placid, New York), where he was the only finisher of six in his age group. This finish earned him a slot for the IRONMAN World Championship in Kona, Hawaii. Another confidence builder.

In October of that year, he completed the Ironman in Kona, finishing 9th of 24 in the men’s 70-74 age group. A month later, he finished Ironman Florida first of fourteen in the same age group. This finish earned him a slot for the 2013 Ironman in Kona.

“Mike Riley knows me well”

In 2013, Howard made his second trip to the “Big Island” of Hawaii for the IRONMAN World Championship. With this and other triathlons leading up to the Kona trip, Howard finished thirteen Ironman races in a row. “Mike Riley [the iconic ‘Voice of IRONMAN’] knows me well,” said Howard. Then, in 2014, he added “Boston Marathon Finisher” to his list of endurance sports accomplishments.

All totaled, Howard competed in 30 to 35 half Ironman and 32 full Ironman triathlons. His half Ironman triathlons were in areas as different as Augusta, Georgia and Argentina, or Mont Tremblant, Quebec, Canada and Muncie, Indiana.

Howard’s full Ironman triathlons included (in alphabetical order):

- Cabo San Lucas, Mexico

- Chattanooga, Tennessee

- Coeur d’e ‘Alene, Idaho

- Cozumel, Mexico (3x)

- Florida (2x)

- Kona, Hawaii (2x)

- Lake Placid, New York (3x)

- Louisville, Kentucky

- Texas (2x)

Of these, he has finished all but five of the half Ironman and 17 of the full Ironman races. Howard chalks up some failures to finish, or DNF (Did Not Finish), to not feeling well or not feeling prepared on race morning. Still, he did not finish others through “overexuberance”. He said, “I tried to do three Ironman triathlons in one month while traveling over 5,000 miles by car, all in my mid-70s. I DNFed all three.”

Life Happens

Over the last two or three years, Howard slowed, deferring many registrations. Recently, he had cataract surgery on both eyes and a second melanoma surgery. The latter forced him to put swimming on hold for several weeks.

Despite deferring his registration for the Ironman Cozumel half Ironman distance this year because of the surgeries, Howard was training for the full distance triathlon in Cozumel set for November. From his knowledge of this course, Howard was confident he could complete this triathlon even though he would have had only about six weeks of swim training after these surgeries.

How Howard Trained for Triathlon

Howard never trained with a coach. However, this was something he was thinking of changing. Howard told me, “not having a coach has cost me a fortune.” It hurt him to spend money on the race registration and travel to the race venue, then not finish the race.

However, this did not mean that he did not prioritize training. Even at this stage in life, Howard trained five days per week. This included biking three times per week, running two to three times per week, and swimming. During the training sessions, he also practiced hydration and eating, race skills critical for long course triathlons.

Advice for Those Thinking of Starting Triathlon Later In Life

According to Howard, starting triathlon later in life may have made it easier. Howard attributes his ability to continue training for and racing in triathlons, at least partially, to his late arrival to the sport. He told me, “When I started, my body was ok. It had not been overused.”

With the need to train as the first advice for others thinking of starting triathlon later in life, Howard offered a second piece of advice: You have to have a will to finish a race despite all the variables that come with multi-sport endurance racing. “You don’t need to be fast, but determined to continue.”

He also told me he had learned to pay closer attention to details of a triathlon he considered doing, especially as he became older. What are race distances? What does the race course look like? Are currents likely to be a factor during the swim? Will hills and/or wind affect the bike leg?

He also suggested that we look at the finisher times from previous races. What are the cut-off times? Can you make the cut-offs? Is this a race you can finish? Or, is it one for which you could win your age group?

Triathlon and Depression

Howard’s motivation to train stemmed from two reasons: a desire to live healthy later in life, and a concern that without regular exercise, he might face another battle with depression. At the time of his death, Howard had a long list of Ironman triathlons he planned to complete. Through these, he hoped to return to Hawaii for the next men’s IRONMAN World Championship in 2026.

I appreciate Howard’s willingness to let us see into to his life before and after triathlon. His transparency can benefit those who also struggle with depression. While one solution seldom fits all situations, endurance exercise in general and triathlon more specifically is a win-win solution for a significant problem that is growing throughout the world today.

A Daughter’s Tribute

Howard’s daughter Lydia wrote a tribute to her father, which she shared with me. Here is part of it:

“If I could see you one more time, I would give you the biggest hug and tell you how much I love you and how proud I am of you for everything you have accomplished in your triathlete/Ironman journey.

Your optimism, determination, and motivation helped inspire me to become a physical therapist because of my awe of what the human body is capable of at any age. This also helped me stay focused in grad school, despite also battling with your son-in-law, Foster’s cancer, and navigating pregnancy, my postpartum journey, and the beginning of motherhood. I graduated with honors, with you, Foster, and your sweet and only baby granddaughter, Ella Sophia, in my arms. This would not have been possible if you hadn’t believed in me and inspired me with your dedication to your sport. You taught me to never give up, and I didn’t. I now enjoy a rewarding career helping others get back to their active lifestyles and reaching their goals.

Ella is now 5 years old and I’m so grateful for the grandfather you became, but I really wish you could watch her grow and be a part of her life. Don’t worry though, we will continue to share stories of you and photos so you will never be forgotten.

I knew that you inspired many athletes, but I did not realize how much of an impact you had until you passed and so many people in your community reached out with their condolences and their stories and memories of you. It really is so touching, I’m so proud of you, and we will miss you dearly. Love you, Dad.

You will be missed by so many. May you rest in peace and stay with us in our hearts forever.”

Click here to read Howard’s obituary.

Have Questions or Comments?

Please leave your questions and comments below.

Comments: Please note that I review all comments before they are posted. You will be notified by email when your comment is approved. Even if you do not submit a comment, you may subscribe to be notified when a comment is published.