Smart Sugar Strategies for Senior Triathletes: Fueling for Endurance After 50

Introduction

I imagine that all of us have heard about the evils of added sugar. According to an article titled Metabolism and Health Impacts of Dietary Sugars published in the Journal of Lipid and Atherosclerosis, “Excessive intake of sugars, especially fructose and sucrose (a dimer of glucose and fructose monomers), are highly correlated with metabolic disease including obesity, diabetes, fatty liver, and cardiovascular disease.”

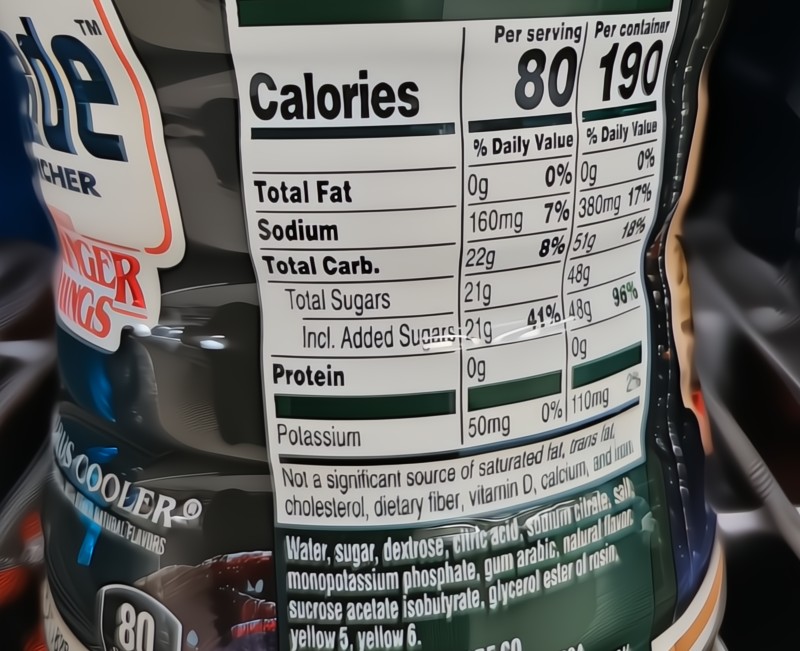

Still, many sports drinks and gels contain significant amounts of added sugars. So, what do we do with this apparent contradiction?

As we continue to push limits in triathlon, duathlon, or aquathlon later in life, our nutritional needs evolve. For the 50+ athlete—man or woman—understanding how your body processes sugar is essential not only for performance but for long-term health.

Age, hormonal changes, and medical conditions like atrial fibrillation (AFib) or fatty liver can alter how we handle sugar. This post breaks down what happens when you consume different sugars, how men and women differ in how our bodies handle them, and how to fuel smarter for your next multisport adventure.

What Sugars Are We Talking About?

The three main sugars we are concerned about in this post are glucose, fructose, and sucrose.

- Glucose, sometimes referred to as dextrose, is the body’s primary circulating sugar. When you eat glucose it’s absorbed in the gut, raises blood glucose, triggers insulin release, and is taken up by muscle, fat, and other tissues (or stored as glycogen).

- Fructose (the other half of table sugar-sucrose-and a big component of high-fructose corn syrup) is absorbed but handled largely by the intestine and liver, not by insulin-responsive muscle. The liver converts fructose into intermediates that can refill glycogen but can also be pushed into de novo lipogenesis (creating fat), raising triglycerides and uric acid in some situations. This is why excess fructose is linked to fatty liver, higher triglycerides and metabolic harm. Fructose-rich added sugars (soda, many processed foods) are more likely to produce unfavorable metabolic effects when consumed in excess compared with the modest fructose in whole fruit. Lest you fall prey to advertising, be aware that some types of agave nectar contain up to 90% fructose and 10% glucose.

- Sucrose (table sugar) contains one molecule of glucose and one molecule of fructose. Your body breaks sucrose into the two component sugars and then processes each as above.

Chemically, these sugar molecules are the same whether they come from an apple or from soda. But in the real-world, they behave differently. Whole fruits contain fiber, water, vitamins, and polyphenols slow absorption, blunt blood-sugar spikes, and provide satiety — reducing total sugar exposure. By contrast, refined/added sugars (sodas, sweets) give a quick, large sugar load with few nutrients. Because of this, refined sugars promote higher post-meal glucose, insulin spikes, and more calories consumed. For most healthy people, eating sugar inside whole fruit is not associated with the same harms as drinking a sugar-sweetened beverage.

What Happens When You Ingest Sugar

When you eat carbohydrates—whether from a banana or a bottle of sports drink—your body breaks them into the simple sugars glucose and fructose.

- Glucose raises blood sugar and provides quick energy to muscles.

- Fructose, handled mainly by the liver, refills glycogen but can also turn to fat if overconsumed.

This is why the type, timing, and source of your sugar intake matter. But, so do other factors, which I address in the next sections.

Men vs. Women: Different Metabolic Responses

Research shows clear sex-based differences in glucose metabolism and cardiometabolic risk, especially around menopause when estrogen levels decline.

- Body composition & hormones: Men typically carry more muscle mass and have a generally higher resting metabolic rate. Women often carry more subcutaneous fat and have different fat-distribution patterns and hormonal influences (especially pre- vs post-menopause). These differences affect how glucose is taken up and used and how insulin sensitivity is maintained. They even how carbs are stored and mobilized.

- Insulin sensitivity: Women (especially pre-menopausal) often maintain somewhat better insulin sensitivity than men. After menopause, estrogen drop can lead to increased insulin resistance, more central fat accumulation, and a higher risk of metabolic issues.

- Fueling strategy: Because of these differences, women may benefit from slightly more cautious carbohydrate dosing (especially added sugars). They may want to rely more on steady, lower-glycemic carbs rather than high sugar loads. Men may tolerate higher absolute carb loads (thanks to more muscle mass) but they too must respect age-related changes.

- Endurance performance implications: For both sexes, during long sessions the gut’s ability to absorb carbohydrate becomes a limiter—so specialized blends (glucose + a bit of fructose) may help. But the ideal ratio/dose may differ slightly by sex (and gut tolerance), so personalized testing – before race day – is key.

Related Post: How to Reduce VO2max Decline for Older Male and Female Triathletes

How Aging Changes Sugar Metabolism

As we age, our bodies gradually become less efficient at handling the sugar we eat. This is true even if we maintain an active lifestyle. Much of this change comes down to shifts in muscle mass, hormones, and daily training patterns. One of the most important factors is the age-related decline in muscle tissue. Muscle acts as a major “sink” for glucose. With less muscle available, especially if strength training has taken a back seat, sugar lingers in the bloodstream longer than it once did.

At the same time, insulin—the hormone that helps move glucose into cells—tends to become less effective. This age-related drop in insulin sensitivity doesn’t necessarily mean someone will develop diabetes. However, it does mean that larger sugar spikes can occur from foods that previously caused little reaction. Hormonal changes amplify this effect in both men and women, especially during and after menopause.

Finally, as many of us naturally shift toward slightly lighter or less intense training loads after 50, we simply burn through fewer carbohydrates each day. That means more unused sugar circulating after meals unless we adapt our nutrition to match our activity level.

Putting this together, older athletes do well to focus on whole-food carbohydrates—fruits, vegetables, and grains—for everyday eating, and to reserve concentrated sugars for training or recovery when they are most likely to be used efficiently. Strength training becomes an essential part of nutritional health, not only athletic performance, because maintaining muscle helps maintain glucose control.

Fructose, AFib, and Liver Health

Fructose plays a unique role in our metabolism, and its relationship with heart and liver health becomes more important as we age. Unlike glucose, fructose is processed almost entirely in the liver. In modest amounts—such as the natural fructose found in whole fruit—this system works beautifully. Problems arise when the liver receives large doses from sweetened sports drinks, processed snacks, or high-fructose sweeteners common in packaged foods.

Over time, excessive fructose can overwhelm the liver’s ability to store or process it, contributing to fat buildup in the liver and increased insulin resistance. These changes don’t just affect metabolism; they spill over into cardiovascular health. Chronically elevated blood sugar and insulin levels create the kind of inflammation and oxidative stress associated with a greater risk of atrial fibrillation.

For athletes with AFib or those who have been told their liver enzymes are “a little high,” paying attention to sugar sources becomes especially important. Natural fructose from fruit is rarely the issue; it’s the repeated, high-dose fructose exposures from packaged foods and sweetened drinks that create trouble. Fortunately, endurance athletes can still use mixed-carbohydrate fueling during long training or racing. The key is to keep these sugary fuels tied to exercise, when your muscles are ready to use the extra sugar rather than pass it on to the liver.

If you have AFib, fatty liver, or metabolic concerns, it’s wise to keep added fructose low and discuss fueling plans with your doctor or a sports nutrition professional who understands endurance training.

Practical Fueling Summary for 50+ Multisport Athletes

Here’s a handy table summarizing best carb practices across daily contexts:

| Context | Best Carb Approach | Fructose Role |

|---|---|---|

| Daily eating | Whole foods (vegetables, whole grains, fruit) | Natural fructose in fruit is fine; avoid added sugars |

| Training < 90 min | Water + electrolytes, such as a banana or other simple carb snack | Minimal added fructose |

| Long training / race | Glucose + small fructose mix (approx. 2:1 glucose: fructose ratio) | Helps carb absorption and energy delivery if your gut tolerates |

| Recovery | Glucose-based carbs + whole fruit | Natural fructose from fruit supports glycogen restoration naturally |

Related Post: Electrolytes: Vital for Hydration and Performance of Senior Triathletes

Remember Your Goal

A major change that occurred during Joy’s and my triathlon adventure was the foods we ate. There were plenty that we gave up. In particular, limiting processed sugar in our diet became part of our triathlon lifestyle.

- Natural over processed: Choose fruit and whole carbs instead of sweetened drinks.

- Age smart: Adjust carb intake to your training volume and recovery rate.

- Gender aware: Recognize hormonal and metabolic differences in fueling response.

- Health aligned: Be extra cautious with added fructose if you have liver disease, AFib, or insulin resistance.

- Train it: Always test fueling strategies before race day.

Your goal isn’t just speed—it’s sustainable endurance and long-term health.

Disclaimer

I’ve written this post based on my best understanding of the science and research I’ve reviewed, as well as my personal experience as a senior triathlete. However, I am not a medical professional. Nutrition, metabolism, heart rhythm conditions, and liver health can vary greatly from person to person.

If you have questions about how this information applies to your own health or fueling strategy—especially if you have atrial fibrillation, liver concerns, diabetes, or other medical conditions—please consult your doctor or a qualified healthcare provider. The information in this post is not intended as medical advice. I am not responsible for any inaccuracies or misunderstandings.

Questions

Is this post useful for your triathlon training and racing? What would make it more valuable? Please share your thoughts in the Comments below.

Comments: Please note that I review all comments before they are posted. You will be notified by email when your comment is approved. Even if you do not submit a comment, you may subscribe to be notified when a comment is published.