Toe Strength, Aging, and the ToePro®: A Senior Triathlete’s Perspective

As we age, the first meaningful losses in lower‑extremity strength often occur at the foot and ankle—particularly in the toes and calves. This decline shows up subtly at first: shorter stride length, reduced push‑off, less confidence when leaning forward, and, eventually, the shuffling gait so common in older adults. For endurance athletes, these changes affect not only balance and fall risk, but also efficiency in walking, running, and even cycling and swimming.

Dr. Tom Michaud, founder of Human Locomotion, emphasizes that toe strength plays a critical role in controlling forward momentum and stabilizing the body during running. When toe strength diminishes, the ability to safely control forward lean—the so‑called “anterior fall envelope”—shrinks. This increases fall risk and reduces propulsion. This framing resonated strongly with me as a senior triathlete, because it explains why foot and toe training can have magnified benefits relative to the small muscles involved.

The Science Behind ToePro

Traditional toe exercises—such as towel curls or marble pickups—primarily strengthen the toes in shortened muscle positions. However, during walking and running, the toes generate force while lengthened, especially during late stance and push‑off. Research cited by Michaud shows that strength gains are highly angle‑specific: muscles trained in functionally relevant, lengthened positions produce more transferable strength.

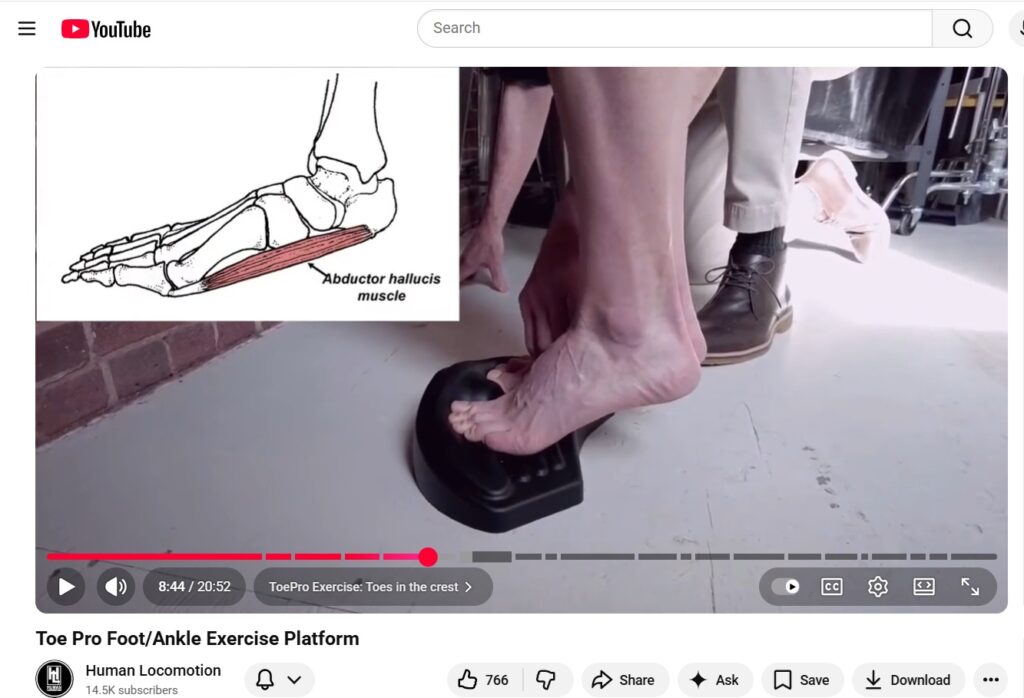

Dr. Michaud designed ToePro explicitly around this principle. By positioning the toes on an angled, compressible surface, the device loads the intrinsic foot muscles and toe flexors in positions that closely resemble real‑world demands. The result is not just stronger toes in isolation, but improved integration of the toes, calves, and lower leg into coordinated movement patterns that matter for balance, gait, and propulsion.

Performing the exercises with slightly bent knees transfers more force through the gastrocnemius to the soleus, working the latter harder. Soleus volume is a predictor of marathon running performance. Weakness of the soleus is a predictor of injury to the achilles tendon and to the knee through valgus collapse.

Doing them with straight knees (standing tall) works the gastroc muscles more selectively. These muscles are the ones primarily responsible for balance.

Related post: Better Balance Makes A Stronger Triathlete

The ToePro Protocol (as Demonstrated by Tom Michaud)

The ToePro protocol (demonstrated in this video) begins conservatively and emphasizes technique over intensity—an important point for older athletes.

The initial phase consists of a warm‑up exercise demonstrated early in Michaud’s video: A controlled forward lean, allowing the toes to press into the foam while maintaining upright posture and relaxed breathing.

After the warm-up, the protocol progress to toe raises, performed both with straight knees (biasing the gastrocnemius) and bent knees (biasing the soleus), followed by isometric holds at the top of the movement. Sustained holds are valuable because they teach the nervous system to maintain force at end range, which is exactly where stability is most often lost with aging.

The guiding principle throughout is restraint: start with low volume, pay close attention to technique, and allow adaptation to occur gradually.

My Experience Using the ToePro

I was introduced to the ToePro by fellow senior triathlete Jim Riley, who encouraged me to “go easy” and use the device daily rather than aggressively. Following that advice, I began by performing the warm‑up exercise and three sets of 10 reps of toe raises with straight knees each day for the first week, focusing entirely on technique and body awareness.

During this initial period, I experienced no pain or discomfort, but I could clearly feel activation in my toes and calves, especially the peroneal muscles. Peroneal muscles are often under‑stimulated in conventional endurance training. Over time, as I gradually increased volume, the most noticeable changes were not dramatic strength gains, but improved control and endurance. Movements that initially felt challenging became more stable and repeatable.

Importantly, the benefits were subtle but cumulative. Rather than a single “breakthrough” moment, the changes showed up as greater ease in daily movement, improved confidence and stability during forward lean, and a sense that my feet were working with me rather than simply contacting the ground.

As I am finishing this post, my routine on five to seven days per week is to complete the warm-up exercise followed by two sets of 25 reps with both bent knees and straight knees (100 reps total). I end each session with a 30-second balance, as prescribed by Dr. Michaud.

Independent Corroboration: Jim Riley’s Experience

Jim Riley, a 76‑plus-year‑old endurance athlete whose story I have previously shared on SeniorTriathletes.com, provided an independent and valuable perspective. Jim noted that toe and calf weakness are often the earliest contributors to age‑related decline in lower‑body function, describing them as a primary reason many older adults’ run gait looks like shuffling.

Over time, Jim progressed to a more demanding routine: toe stretches followed by 30–40 toe lifts with straight knees, holding the final repetitions for five seconds each, and then another 30 lifts with bent knees. He reports that when he began, he was unable to sustain those final isometric holds—a limitation that resolved only after months of consistent practice.

While Jim acknowledges that objective measurement is challenging, his qualitative outcomes are compelling: fewer foot and calf issues, a more natural walking gait, reduced effort when moving, and even improvements in swimming kick mechanics. These observations align closely with the physiological rationale Dr. Michaud presents.

What This Means for Senior Triathletes

The ToePro is not a quick fix. As with strength training in general, its benefits may not be immediately obvious. For senior triathletes, its value lies in restoring and preserving a foundational capability that underpins everything else we do: the ability to generate and control force through the toes.

The key takeaways are straightforward:

- Toe strength declines early with age but remains highly trainable.

- Training in lengthened, functional positions matters.

- Daily, low‑intensity consistency appears more effective than aggressive loading.

- Improvements may show up first as better control and efficiency rather than raw strength.

Looking Ahead

This review focuses exclusively on the ToePro. I strongly encourage you to watch the first 13 minutes of the linked video.

For senior triathletes interested in longevity, balance, and efficient movement, targeted strengthening of muscles below the knee deserves far more attention than it typically receives. The ToePro provides a practical, physiology‑based way to address that gap.

Human Locomotion’s Rockboard, which Jim also recommended and which I have not yet begun to evaluate, will be reviewed separately to maintain clarity and objectivity.

Questions/Comments

What did you find most interesting about this post? What questions arose as you were reading it and/or watching the ToePro video? Share your thoughts in the Comments below.

Comments: Please note that I review all comments before they are posted. You will be notified by email when your comment is approved. Even if you do not submit a comment, you may subscribe to be notified when a comment is published.

Editor’s Note

The ToePro used for this evaluation was provided by Human Locomotion for review purposes. Human Locomotion had no editorial input into this article, and all observations and conclusions reflect my independent experience and assessment as a senior triathlete.