The 5 Things New Triathletes Over 50 Must Get Right

Lessons from Laura Rossetti, four-plus decade triathlete and coach

Starting—or restarting—triathlon after age 50 is not about doing everything right. It is about getting a few critical things right early, the things that make the difference between struggling through the process and finishing races with confidence and enthusiasm.

Few people have a longer or more instructive view of that process than Laura Rossetti. Laura began racing triathlons in 1985 at age 29, long before coaching, data platforms, or training plans were widely available. More than 40 years later, she is still training, still coaching, and still racing—now in her 70s.

Her perspective is rare because it is not theoretical. She has lived through the sport at multiple ages and stages, and she has seen what helps athletes stay—and what causes them to disappear.

When asked for the five most important things older athletes must get right, her answers were grounded in experience, not trends.

Laura’s Top 5 List for New Triathletes

#1. Find Your Group: Everything Is Easier To Accomplish With Your Tribe.

“If you don’t always have a community, you just don’t do the work.”

Laura places enormous importance on training partners and community—not as a nice bonus, but as a requirement for consistency and enjoyment.

When she moved to Georgia in her early 50s, she “didn’t know a soul. Not one soul.” What made the difference was finding people through masters swimming and local training circles. Without that group, she said training would have been “really challenging and tough,” and she doubts she would have enjoyed the sport nearly as much.

Laura believes that building community gets harder with age. “It’s much harder to make connections when you’re 50, 60, 70. You have to put yourself out there or it’s not going to happen.”

For athletes over 50, community provides accountability, shared learning, motivation, and emotional support. Bike shops, running stores, pools, gyms, and even casual conversations with people who share an interest in swimming, biking, or running are all natural places to begin building that community.

Through our discussion on this point, I (Terry) realized that even though I self-coached, I was never truly alone. My community included the friend who talked me into doing my first triathlon, my daughter, and the people I met at my local bike shop, pool, and gym. It also included countless triathletes I met only briefly—often just once—who were generous with their time, advice, and encouragement.

#2. Hire a Coach—or Train with People Who Truly Know the Sport

“You don’t know what you don’t know.”

Laura raced for years without a coach because, when she started, coaches barely existed. Today, having a coach—or an experienced triathlete—to help guide training is a must-have for many athletes. For older athletes balancing work, family, stress, and recovery, a coach provides two keys to success: accountability and knowledge to define training that is objective, enjoyable, and realistic for the athlete’s life.

One story Laura shared illustrates the value of objectivity. A fellow coach recently tested a new athlete who believed she was “really fit.” After bike and run testing, the coach told her she was not as fit for triathlon as she thought. The data simply did not support her self-assessment.

As Laura explained, “Without someone looking at your data, you have no ability to be objective about it.” A good coach—or knowledgeable training partner—can help interpret data, adjust training when life intervenes, and reduce the risk of boredom or burnout.

Communication with your coach is critical. Look for a coach with whom you can communicate easily and honestly and are willing to follow. Read reviews or talk with clients of potential coaches. Your coach must be a fit for what you are looking for and how you think and live—not just your age.

#3. Do Not Let Data Overwhelm You

“Data is valuable; the only way to know if you’re improving is with data.”

Laura has completed Ironman races with little more than a heart-rate monitor. While she values modern tools, she cautions beginners against starting with everything at once.

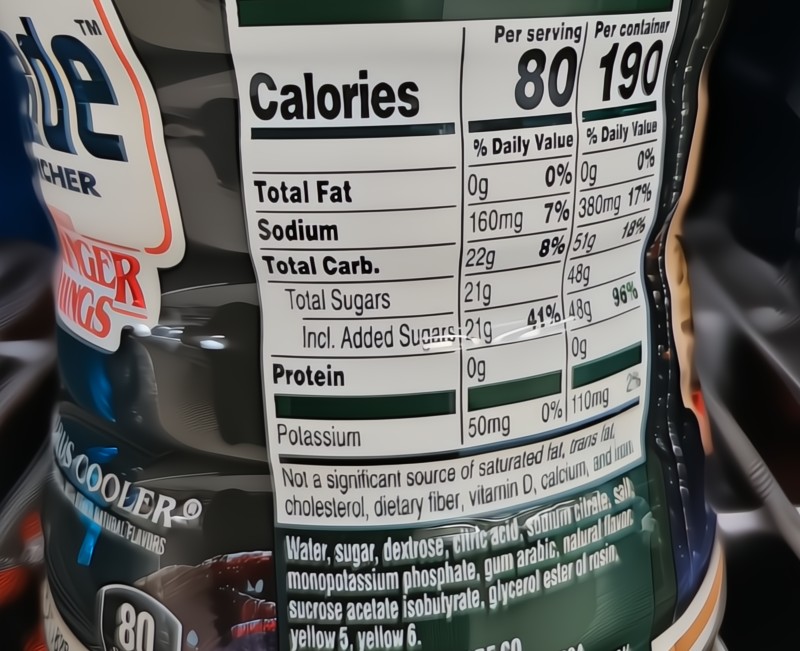

For athletes over 50, she believes the most useful early metrics are the minimum needed to let you know if you are improving. This can include functional tests such as the time to complete a known distance, a test easily done for running and swimming. A coach will check to see if you are completing these in the same or lower time after the same amount of rest.

Heart rate is another useful metric. Training with a heart rate monitor can reveal issues athletes might otherwise miss, such as fueling problems, electrolyte imbalance, or accumulated fatigue. On the other hand, power meters and advanced analytics can come later, once the basics are understood.

Laura also emphasized the value of using Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE)—learning what easy, moderate, and hard actually feel like. Without that internal awareness, numbers can become confusing or misleading.

“The real value of whatever metrics you use comes from knowing how to interpret them and improve them over time.”

#4. Set Goals—Especially Early On

“I just want to see you cross the finish line loving what you just did.”

For first-time triathletes, Laura believes “finishing the race with a smile” is the right goal. Enjoyment, pride, and learning matter more than time goals early on.

Many athletes over 50, she notes, never had the opportunity to participate in endurance sports earlier in life. For them, the first race is about discovering what they are capable of—not proving anything.

She stresses the important of perspective for those beginning in the sport. Completing a triathlon—at any pace—is something most people will never attempt, and that accomplishment alone deserves recognition and gratitude.

Over time, goals evolve. Early success builds confidence, which leads to new challenges and deeper commitment. Without goals, Laura said plainly, “I don’t know how to get good without having them.”

#5. Do Not Jump to Ironman Without the Process

“You need to start small to get big.”

Laura shared the story of a friend who decided at age 50 to do an Ironman without ever having completed a triathlon. Against the odds, he finished—but she is clear that he is the exception, not the example.

He had unusual durability, few outside obligations, and informal mentorship. Most athletes do not.

For Laura, the real risk is not failing to finish—it is shortening an athlete’s relationship with the sport through injury, burnout, or disillusionment. She strongly encourages progression through shorter distances to learn pacing, fueling, and recovery before attempting Ironman.

Through this progression, an athlete will also learn about themself. “Are you a slow twitch or fast twitch person?” In other words, are you wired for speed or endurance. If the former, the Ironman distance may not be for you.

Longevity, in her view, is the true measure of success.

The Long View

What stands out most about Laura Rossetti is not her podium finishes, but her continuity. She continues to race each year. She still trains with people she met decades ago. And, she cherishes the friendships the sport has created and continues to create.

Triathlon can be a lifelong pursuit, even when you start—or restart—after 50. But only if you respect the process, surround yourself with people, and make decisions that support the long view.

As Laura’s experience shows, how you begin often determines how long you stay.

What Questions Do You Have For Laura?

Leave your questions and comments for Laura in the Comments section below.

Comments: Please note that I review all comments before they are posted. You will be notified by email when your comment is approved. Even if you do not submit a comment, you may subscribe to be notified when a comment is published.

Editor’s Note

Thank you to Dr. Sarah Gordon for introducing me to Laura Rosetti. You can learn more about Laura’s triathlon journey at The PhD Journey Podcast, Episode 19 at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c3tvxaadYlU.