Ask Our Coaches: Will A New Bike Help With Knee Pain?

Question

A veteran, 68 year-old female triathlete sent me the following question for our coaches:

“I have a Trek 2500 (yes, it’s a dinosaur). I have been doing triathlons for 25 years but my knees are starting to hurt when pushing on the bike. Are there bikes you could recommend that require less pressure on the knees (I am 68).”

Coach Tony Washington’s Reply

Hi! First off, congratulations on 25 years of triathlons—that’s an incredible achievement, especially at 68. Your bike has been an amazing partner on so many adventures.

Your Trek 2500 is indeed a classic (it dates back to the ‘80s and ‘90s with its aluminum frame and more aggressive road geometry), but it’s no surprise knee issues are cropping up after all that mileage.

Knee pain in cycling often stems from overuse, improper biomechanics, or age-related changes like reduced joint lubrication or arthritis. The good news is there are plenty of ways to address it without hanging up your wheels. I’ll focus on bike recommendations that could ease knee pressure, while also covering fit adjustments, crank length, pedals/shoes, saddles, and other factors as you requested.

Remember, this isn’t medical advice—consult a doctor or physical therapist to rule out underlying issues, and consider a professional bike fit (around $150–300) for personalized tweaks.

Understanding and Reducing Knee Pressure in Cycling

Before jumping to new bikes, let’s tackle why your knees might be hurting and how to minimize strain. Cycling is generally low-impact and great for knee health because it builds strength without pounding, but pushing hard (like in tri bike segments) can overload the patella (kneecap) or surrounding tendons. Common culprits include a saddle that’s too low/high, misaligned cleats, or an aggressive posture that forces your knees into extreme flexion.

Key Adjustments Beyond the Frame

Bike Fit: Start here—it’s often the fix for 80% of cycling knee pain. Aim for a saddle height where your knee has a 25–35-degree bend at the bottom of the pedal stroke (leg almost straight but not locked). If it’s too low, you’ll overload the front of the knee; too high, the back. Fore/aft position matters too: Your knee should align over the pedal spindle when the crank is horizontal. A pro fitter can also check for leg length discrepancies or hip imbalances common in seniors.

Crank Length: I’ve moved most of my athletes to shorter cranks. I’m 6’5” and use 160mm cranks. I have set all time power PRs from 5 secs to 5 hours. One of my athletes is 5’5” and switched to 145mm. This helped he correct knee tracking and much better hip movement. Shorter cranks reduce hip angle at the top of the pedal stroke. Less strain when your hips and knees are at most extreme angles of the pedal stroke can really help with the pain.

Shoes and Pedals: Clipless pedals are great for efficiency in tris, but poor cleat setup can cause pain. Position cleats so your feet are neutral (not toe-in/out), and consider float (e.g., 6–9 degrees) to allow natural knee movement. For less pressure, try pedals with more float like Speedplay or switch to flat pedals temporarily for training. Shoes should be stiff-soled but comfy—brands like Shimano or Specialized offer wide fits for aging feet. If you have arthritis, look for vibration-dampening insoles.

Saddle/Seat: Your Trek’s saddle might be too narrow or firm after years of use. Opt for a wider saddle (140–160mm) with a cutout to reduce pressure on soft tissues. A good bike shop can measure your sit bones and should have loaner models to try before you buy. Models like the ISM, Specialized Power or Bontrager Verse are popular for endurance. Raise the handlebars or add aero bar risers for a more upright posture, which reduces knee flexion and forward lean.

Other Tips for Reducing Knee Pain

- Warm up with 10–15 minutes of easy spinning and stretches (quads, hamstrings, IT bands).

- Pedal at a higher cadence (80–100 RPM) to “spin” rather than mash—it’s easier on joints.

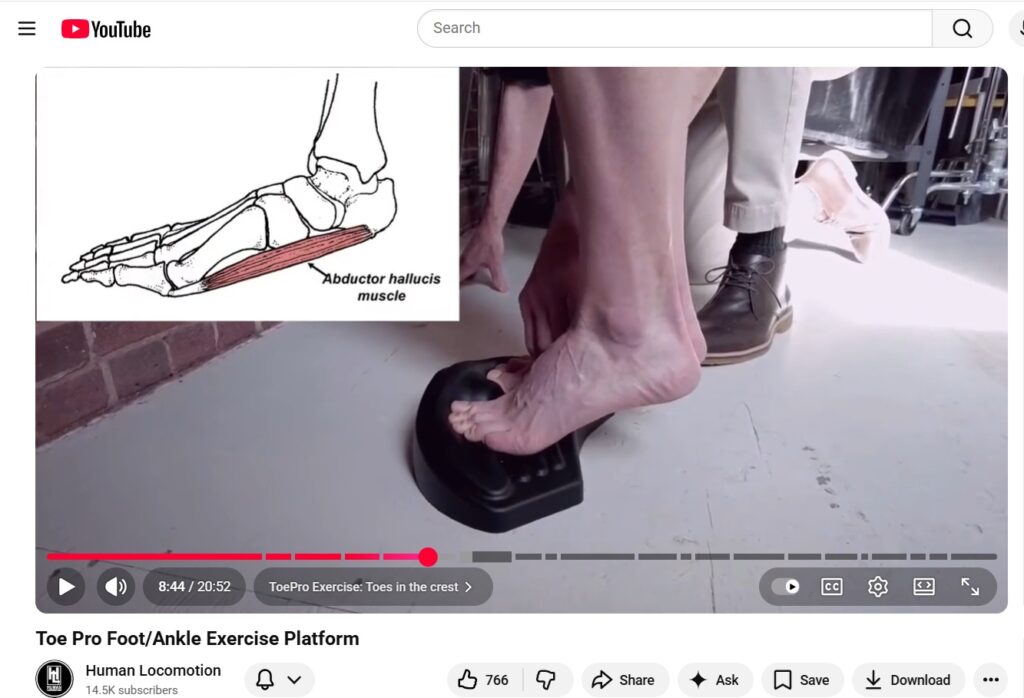

- Strengthen supporting muscles with off-bike exercises like squats, lunges, or clamshells twice a week.

- Build mileage gradually (no more than 10% increase per week), and use RICE (rest, ice, compression, elevation) for flare-ups.

Bike Recommendations for Less Knee Pressure

These tweaks could make your current Trek more knee-friendly, especially for training. If pain persists, a new bike with geometry that promotes less aggressive positioning might help.

If the above tweaks aren’t working. Consider these two types of bikes. They are available at your local bike shop. Ride as many as you can to see if they fit better.

- Endurance Road Bikes: These have relaxed geometry (taller head tube, longer wheelbase) for upright riding, reducing knee bend and pressure. Great for tri training and races with aero add-ons.

- Hybrid or Comfort Bikes for Training: More upright than road bikes, with wider tires and cushier saddles—perfect for knee relief during build-up miles or on your indoor trainer.

In Conclusion

If you’re sticking to competitive tris, an endurance road bike with aero tweaks might be the sweet spot—test ride a few to see what feels best. Many shops offer senior discounts or demo days. Keep racing strong; with these changes, you could add another 25 years!

Related post: Five Factors For Selecting a Bike For Triathlon

Cheers,

Tony Washington

Senior International Captain/Grandpa

Founder and Head Coach – Team No Coasting

Certified IRONMAN U and TriDot Coach

Certified TriDot Pool School Lane Lead

(972) 533-8583

https://app.tridot.com/onboard/sign-up/tonywashington

Questions

Do you have questions for Tony about selecting a triathlon bike? Post them in the Comments below.

Comments: Please note that I review all comments before they are posted. You will be notified by email when your comment is approved. Even if you do not submit a comment, you may subscribe to be notified when a comment is published.