Should Senior Triathletes Track Heart Rate Variability?

We know that recovery is critical for older triathletes. If heart rate variability can measure how well we have recovered, can it also help senior triathletes recover more completely?

My First Experience With Heart Rate Variability

Joy and I started using a new Sleep Number bed recently. While reviewing our sleep scores from the Sleep IQ app, it surprised me to see Heart Rate Variability, or HRV for short, as a metric for sleep quality.

I had previously come across articles about HRV in relation to triathlon training. However, I had paid little attention since there seemed to be a fair amount of controversy about HRV measurement and its usefulness for training.

In this post, I share what I have learned about the current state of heart rate variability for triathlon training and how it may be useful for senior triathletes.

What Is Heart Rate Variability (HRV)?

According to Sleep Number’s Sleep IQ app, “Heart rate variability (HRV) is the measure of different time durations between each heartbeat.”

For example, a heart rate of 60 beats per minute suggests that the heart beats an average of once each second. However, the actual time between beats varies, sometimes more and sometimes less, around the average time.

The variation between heartbeats comes from our autonomic nervous system’s (ANS) effort to fine tune our bodily functions in response to various sources of stress.

The ANS helps us maintain balance through its two branches:

- sympathetic nervous system (SNS) which manages our ‘fight or flight’ stress response needed for short-term survival.

- parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS), which handles our ‘rest and digest’ responses required for long-term survival.

The commonly reported value for HRV is the standard deviation of the variations in the time between heartbeats. Another name for this is the standard deviation of normal-to-normal inter-beat intervals (SDNN) measured in milliseconds. (Don’t worry if your memory of statistics is rusty.)

What Can Senior Triathletes Learn From Heart Rate Variability?

The SleepIQ app adds, “A high HRV is good. High HRV means high energy, good recovery, enhanced cognitive performance, and balance of heart and mind. Monitor stress and well-being by monitoring your heart rate variability.”

Under most conditions, high HRV shows that your body can adapt to many types of changes. Conversely, lower HRV suggests a less flexible body, one currently experiencing or on the verge of health problems.

According to the Cleveland Clinic, low HRV is “also more common in people who have higher resting heart rates. That’s because when your heart is beating faster, there’s less time between beats, reducing the opportunity for variability.”

However, there are some exceptions, which complicate use of this metric. High HRV can also occur when the stress from training has exceeded our ability to recover, at the onset of illness, and because of changes in sleep and exercise patterns.

Can We Influence Our HRV?

If a high HRV is generally better, what can we do to increase it?

As illustrated in the table below, there are many factors that affect HRV. Some, like diet and exercise, we can control. Others, such as age and gender, we cannot.

| Lifestyle | Training | Biological | Mental Health | Environmental |

| Sleep | Volume | Age | Stress | Chemical Exposure |

| Nutrition | Intensity | Gender | Depression | Electromagnetic Field (EMF) Exposure |

| Exercise | Overall Fitness | Ethnicity | Anxiety | Air Quality |

| Alcohol Consumption | Unfamiliar Stimuli | Genetics | Emotions | Work Schedule |

| Tobacco & Drug Use | Illness | Meditation | Use of Vibrating Tools |

Getting good sleep, eating a heart-healthy diet, avoiding unhealthy environments whenever possible, and training at a level appropriate for our level of fitness are actions we can take to increase our HRV.

In addition, alternative medicine approaches, including biofeedback training, may be helpful. Biofeedback is a method mentioned by Cleveland Clinic for improving heart rate variability for those who suffer from stress, emotional disorders, physical issues such as hypertension, and addictions.

Related post: 11 Passages to Read to Help Fight Worry

The numerous factors affecting HRV explain why it is best to track HRV during sleep, that is when many of the factors will not affect the measurement. If manual measurement is required, then measure HRV immediately upon waking.

HRV For Triathlon Training

HRV is already recognized as a tool for assessing the risk of sudden cardiac death. Meanwhile, measurement of HRV for applications like endurance training is still emerging, albeit quickly.

For example, in the past few years, HRV measurement has advanced from requiring ECG sensors to using a cell phone camera. Its use has expanded to include guiding day-to-day triathlon training.

Earlier Research Demonstrated the Potential for HRV as a Training Metric

In principle, because HRV measures the effects of mental and physical stress, it should be an indicator of training stress.

A 2016 report titled “Detailed heart rate variability analysis in athletes” documented the higher HRV for elite and masters triathletes compared to “healthy, but not athletic” adults. The author’s conclusions included: “Further investigations are needed to determine its [HRV’s] role in risk stratification, optimization of training, or identifying overtraining”.

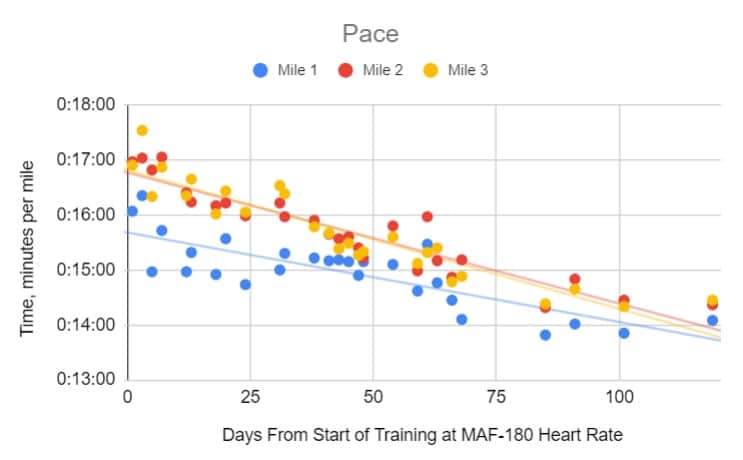

In another 2016 report titled “The role of heart rate variability in sports physiology“, the author noted that studies in which HRV was used to monitor exercise training “suggested that monitoring indices of HRV may be useful for tracking the time course of training adaptation/maladaptation in order to set optimal training loads that lead to improved performances”. In other words, HRV could be used to optimize training load and recovery.

Triathlete and triathlon coach Dr. Dan Plews describes himself as “a big proponent of using daily, resting measures of heart rate variability (HRV) to help guide day-to-day training decisions”.

Plews completed his PhD on heart rate variability in 2017. In an interview with Mikael Eriksson on the Scientific Triathlon podcast during the same year, Dr. Plews shared some results of his research.

He stated that our resting HRV, that measured first thing after waking, can tell a lot about how well we have recovered. However, since many factors affect this single measurement, it is better to look at the trend in HRV, typically over seven days.

HRV Measurement for the Amateur Athlete

Over the last five years, HRV has grown from a research topic to a metric used by amateur athletes and fitness enthusiasts to plan their training schedules.

HRV measurement is more accessible. Today, you can measure your HRV with a smart bed, such as Sleep Number. You can also measure HRV with your smartphone or a host of wearable devices, like smart watches and finger rings.

Smartphone apps are also more capable of interpreting and summarizing the measurements.

For example, the following is from a post on the EdureIQ blog. “HRV, which can be measured reliably and with validity using a smartphone application, gives us insight into the functioning of our autonomic nervous system, and trends in our daily, resting HRV give us insight into the balance between stress and recovery; downward trends in HRV, or big daily fluctuations in HRV, tell us that stress and fatigue is accumulating”.

One word of caution. There is significant disagreement about the accuracy of devices that use light, rather than electrical impulses, to measure heart rate through the skin. It is not clear whether this is based on fact or marketing tactics.

However, the consensus is that the day-to-day trend in HRV is more useful than an isolated HRV measurement, even if made during sleep or immediately after waking.

Some Suppliers of Sensors and Software for HRV

If you are interested in exploring heart rate variability for your training, look at these suppliers of devices and software for measuring and reporting it.

I would also like to hear (in the Comments below) what you learn and/or decide.

Elite HRV

This company supplies a free cell phone app for use with a select list of heart rate chest strap which they have qualified for HRV measurement.

Garmin

Garmin supplies sports watches, including heart rate monitoring devices and apps for measuring and tracking HRV.

HRV4Training

This business provides a paid smartphone app described to provide “Heart Rate Variability (HRV) insights to help you quantify stress, better balance training and lifestyle, and improve performance”.

ithlete

According to the ithlete website, “A convenient one minute daily measurement with ithlete will provide you with all the information you need to tailor your training and recovery ensuring maximum performance.”

Polar

This leader in heart rate measurement offers the Polar Flow app for use with one of their heart rate straps to measure HRV.

Whoop

Whoop uses a wearable device to measure heart rate, heart rate variability, breath rate, and other factors (e.g. skin temperature) to calculate a degree of recovery.

Is Tracking Heart Rate Variability Helpful for Senior Triathletes?

There is growing evidence that heart rate variability is useful for tracking training stress and recovery. Measuring HRV is no longer an issue. However, interpreting the results may still be a challenge because of the many factors that affect day-to-day and even longer trends in HRV.

What do you think about using HRV as a metric for monitoring your triathlon training and recovery?